Please note that this article contains historical terms which may be offensive to modern readers

The mental health of our forebears was just as fragile as our own. Common problems such as bereavement, the breakdown of a marriage, financial worries and stress caused by overwork could spiral out of control, leading to debilitating mental illness. Lacking other options, many of our ancestors with mental illness were confined to institutions known as lunatic asylums.

Until the middle of the 18th century London’s Bethlem Hospital (colloquially known as Bedlam) was the UK’s only public lunatic asylum. There were private ‘madhouses’ for those who could afford to pay for their treatment, but they had a reputation for profiteering and neglect. Most ‘lunatics’ were cared for by their families or the parish, and were often locked up if thought dangerous.

From 1808 local authorities in England and Wales were encouraged to build county lunatic asylums for mentally ill pauper patients. After the 1845 Lunatics Act and Pauper Lunatics Act, establishing these asylums was made compulsory. Five years later, 24 such institutions had been founded to accommodate an average of about 300 lunatics each. By 1890 the number had increased to 66 asylums, with capacity for more than 800 lunatics in each. Most ‘harmless’ lunatics were still accommodated in workhouses because it was cheaper to do so.

In Scotland before 1855, there were seven large mental hospitals and a network of smaller private ones. Under the 1857 Lunacy (Scotland) Act, new asylums run as part of the Poor Law were built and administered by parishes. The first opened in 1863, and a further 18 had been established by 1910.

In addition to lunatic asylums, there were large-scale charitable asylums for patients labelled as ‘idiots’ and ‘imbeciles’; today, they would be described as having learning disabilities. By the 1860s, there were five such institutions in England and Wales, three in Scotland and one in Ireland. In the 1870s, three state-funded asylums for ‘idiots’ and ‘imbeciles’ were founded through the Metropolitan Asylums Board. There were insufficient places in ‘idiot asylums’, so people with learning disabilities were usually accommodated in Poor Law institutions; those considered more troublesome were sent to county lunatic asylums instead.

Originally, Victorian asylums were designed to cure the mentally afflicted where possible, not simply to incarcerate them. In many cases, time away from the stresses of daily life with fresh air, work therapy and nutritious food could significantly improve a person’s mental wellbeing.

However, the number of asylum patients grew considerably during the 19th century, with far fewer cases being discharged. By 1914, more than 100,000 patients were accommodated in over 100 mental institutions across the UK. Asylums had become places to confine chronic, incurable patients with no hope of recovery.

Where to find records from lunatic asylums

Asylums for ‘lunatics’ and ‘idiots’, as well as licensed madhouses, were regularly inspected by the Lunacy Commission. Meticulous record-keeping was required by law, which is why we have such detailed records today. However, you’re more likely to find documents if your ancestor was in a county lunatic asylum rather than a private one. Although it can be distressing to discover that your forebear was in an asylum, the records provide illuminating details about their family background, mental health and treatment.

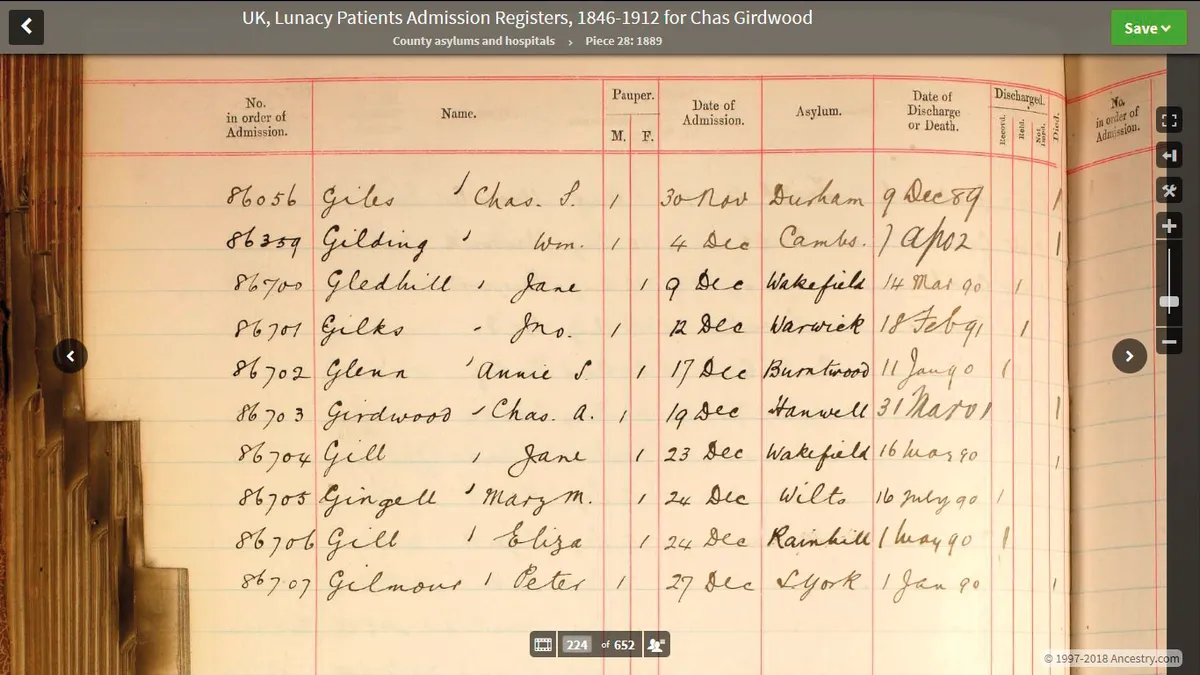

For England and Wales, start with the Lunacy Patients Admission Registers for public and private asylums, beginning in 1846. Catalogued under MH94, the originals are at The National Archives in Kew but Ancestry has digitised them for 1846–1921. The records’ information includes the patient’s name, the institution, the date of admission, and the date of discharge or death. Be aware that if a patient was treated in more than one asylum, there may be omissions in the registers.

The equivalent record for Scotland is the General Register of Lunatics in Asylums from 1858; this lists all asylum patients, including those admitted before 1858 who were still being treated. The National Records of Scotland has the originals, catalogued under MC7. For patients admitted after 1 January 1858, there are detailed admission forms under MC2. Scottish Indexes has indexed both record sets. You can search for free and download documents for a small fee.

Once you know where your ancestor was treated, you can find out whether patient files still exist. Most lunatic asylum records are held in local archives, and you can discover what’s available by searching the Hospital Records Database.

Three main types of record were kept: admission registers; discharge/death registers; and patient casebooks and/or case files. The documents are more detailed from the 1840s onwards. The admission registers include the patient’s full name, age and marital status; place of abode and occupation; date of admission and social class (pauper or private); mental and physical condition; the diagnosed mental disorder and supposed cause; plus religion and education.

Asylum patients were bathed on arrival, and an examination was made of their mental and physical condition. Afterwards, their mental illness was diagnosed; this might be melancholia, mania, dementia or amentia (‘idiocy’ or ‘imbecility’). The admission registers also state whether the patient was recovered, relieved or not improved when discharged, or whether they had died. Sometimes, more detail is given in the relevant discharge registers.

If your ancestor’s casebook has survived, then you will find regular reports about their health, behaviour and treatment in the asylum. From the 1870s onwards, there might even be photographs of patients. Other useful records include annual reports and visiting committee minutes.

An increasing number of asylum records are coming online. The Wellcome Library is working with others to digitise records from a range of asylums including The Retreat in York and Gartnavel in Glasgow. The Wellcome Trust also funded the A Case for the Ordinary project, which involved putting records of doctors, patients and staff from Staffordshire’s county asylums online. Findmypast has the collection ‘London, Bethlem Hospital Patient Admission Registers and Casebooks 1683–1932’; it also has transcripts for Prestwich Asylum Admissions (1851–1901), South Yorkshire Asylum Admissions (1872–1910) and Bexley Asylum Minute Books (1901–1939).

Ancestry has digitised the Criminal Lunacy Warrant and Entry Books (1882–1898) and some early Criminal Lunatic Asylum Registers (1820–1843). It also has the Fife and Kinross Asylum Registers (1866–1937) and indexes of St Lawrence’s Asylum Registers, Bodmin, Cornwall (1840–1900).