Crowds queuing outside Sheffield’s theatres and music halls in Victorian times were entertained by Italians singing folk songs and playing the accordion.

For just a few pennies they could feast on delicious ice cream made to an Italian recipe.

A ‘Little Italy’ had formed in Sheffield’s West Bar area, and its inhabitants were keeping their culture alive.

The story of their journey from the poverty-hit villages of Italy to the industrial powerhouse of Sheffield is one of strife, determination and passion.

Julie Fawcett is a direct descendant of one of the West Bar families, and she has reunited the community once more through a remarkable project. It hasn’t been easy, however, because Italian roots can be hard to trace.

Inspired by Angelina

“My paternal grandmother’s name was Angelina Pelligrino, so I always knew we had Italian roots,” Julie explains. “She was born in Sheffield in 1907, and married Cyril Withers.

“Every week we would have dinner at Angelina’s house. She would tell us stories of her childhood, and of when she worked in a delicatessen in town called Pizutti’s.

“I began researching Angelina’s family tree 11 years ago, and found an elaborate network of Italian ancestors in Sheffield.

I wanted to know why they came to Britain, and why they clustered in West Bar.”

During the 19th century, huge numbers of Italians emigrated to Britain and the USA. Italy’s population had grown swiftly, and agriculture couldn’t keep pace. Southern Italy, where the land was rocky and arid, was hardest hit.

Many Italians lived by subsistence farming, picking mushrooms and chestnuts, or making baskets and cribs to sell at local fairs. If the crops failed, they were forced to move to the more affluent north – or emigrate.

Strolling artists, street musicians, artisans and farmers travelled to Britain. Some endured a choppy sea journey in cramped, unhygienic conditions, while the poorest crossed Europe on foot. After working a season in Britain, many Italians returned to their home villages for the harvest.

However, by the 1860s ice-cream sellers and organ-grinders began to stay longer in Britain and marry into the local community. Other family members would join them, creating a pattern of chain migration.

“Few of the Italians spoke a word of English, so they gravitated towards established Italian communities,” Julie reveals. “Community leaders, known as padrones, would help the new arrivals with documents, accommodation and work. Little Italys sprang up in towns across Britain.”

Italians arriving in Sheffield were so poor that they congregated in the West Bar slums, which had been condemned before they even arrived. Some scraped a living as musicians, circus performers or barkers calling out fairground attractions. Children worked as street entertainers, exhibiting monkeys and white mice.

Little Italys sprang up in towns across Britain

A number of newcomers found employment in Sheffield’s steel and cutlery-making industries, and the artisans among them created beautiful marble mosaics. “The West Bar community played an integral part in Sheffield’s development.”

Julie’s Pelligrino family emigrated from Puglia, the ‘heel’ of the ‘boot’ in Italy. “Family legend has it that my great grandfather Antonio Pelligrino met his future wife Louisa Lagoria on the crossing. Louisa’s family wanted to emigrate to America, but she was so seasick that when they arrived in Britain she refused to get on another boat.”

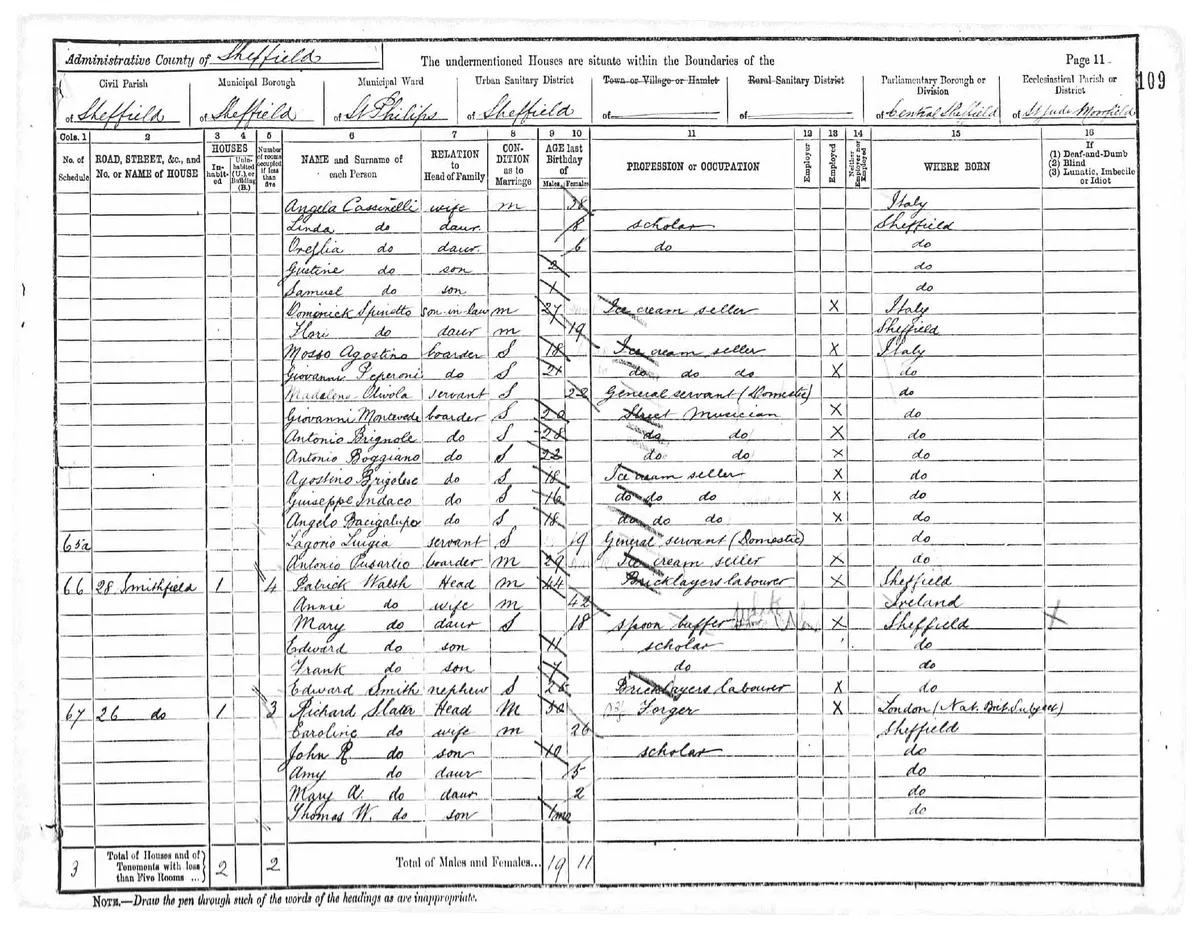

At the time of the 1891 census Louisa was boarding in West Bar with Antonio Cassinelli, who was one of the foremost padrones.

Slumming it

“The West Bar slum had back-to-back houses, and high crime rates. Some houses had separate kitchens, living rooms, bedrooms and outside privvies. However, this was an improvement on conditions at home. Italian peasants lived in huts with straw roofs and no flooring, while some shared their home with farm animals. Bread and polenta were the staples of life, supplemented by beans, oil and vegetables.”

In the 1911 census, Julie’s forebear Antonio was working as a street organist and living in three rooms with Louisa, their two daughters, three sons and a couple of lodgers. West Bar had the highest infant mortality rates in Sheffield and, tragically, the couple had already lost five children. They must have missed loved ones back in Italy, especially when faced with the heartache of bereavement. West Bar’s Little Italy was their haven.

“The Italians were a novelty to begin with. Over the years, however, locals began to view them with suspicion. Some people associated Italian padrones with the Mafia, and this stereotype lasted for decades.”

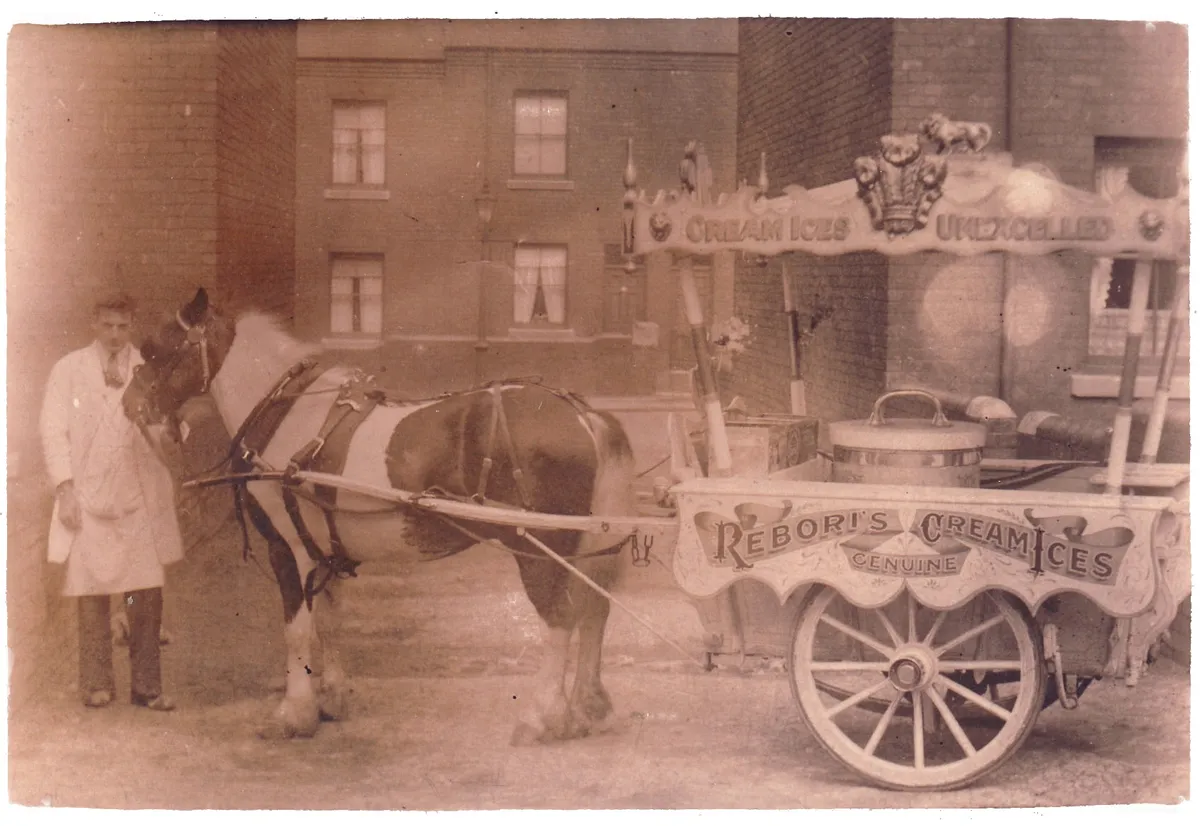

The ice-cream trade proved lucrative for a number of West Bar families, and their names became as famous as their ices. “Luigge Cuneo established a thriving business in Sheffield, with a shop in Devonshire Street called the Ice Cream Saloon. It had an American soda fountain, and a window filled with boiled sweets. Cuneo’s is still producing ice cream 155 years later.”

Meanwhile the Buffalaro family made ice cream in their own West Bar factory. Some of their descendants remember the scent of vanilla wafting around the streets.

Uncovering the network

During the late 19th century, more Italians emigrated to West Bar and they began marrying back into their community, which centred on the Catholic St Vincent’s Church. A vast network of ancestors emerged in Julie’s research.

“They were close-knit, and it became hard to separate one family from another because of intermarriages. What’s more, the patronymic naming tradition meant there were often a number of boys in one family with exactly the same name.

“Also, British recorders struggled with Italian names and spellings, which made things even more confusing. For instance, on one record ‘Augustino Franchetti’ became ‘Gausto Chowsetti’.”

Over time the West Bar families dispersed across Britain, and this signalled the demise of this particular Little Italy. During the Second World War the community was stigmatised, and further residents moved or changed their name. As a result descendants of the West Bar Italians can now be found across the world.

As her passion for genealogy grew, Julie decided to help other people trace their Italian roots. She set up a website, West Bar Italians, which includes marriages, cemetery records and evocative old photos.

Julie’s project snowballed when she began contacting other West Bar descendants on forums, and exchanging emails. “In March 2009, I travelled to Sheffield to meet eight other descendants at St Vincent’s Church. We were shown around by Vincent Hale, the custodian of the church records who saved them from being lost when the parish moved.

“I stood in the church, closed my eyes and absorbed the history that surrounded me. I thought of my ancestors who had married or been christened there, and the hundreds of other Italian families who had passed through. It was a privilege to stand where they had stood, and to be part of their achievements.”

The Franchetti, Rebori, Granelli and Pelligrino families were all represented at the get-together. “None of us had met before, but the conversation flowed as though we were old friends. Our ancestors would have been proud of us."

Gail Dixon is a writer and regular contributor to Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine