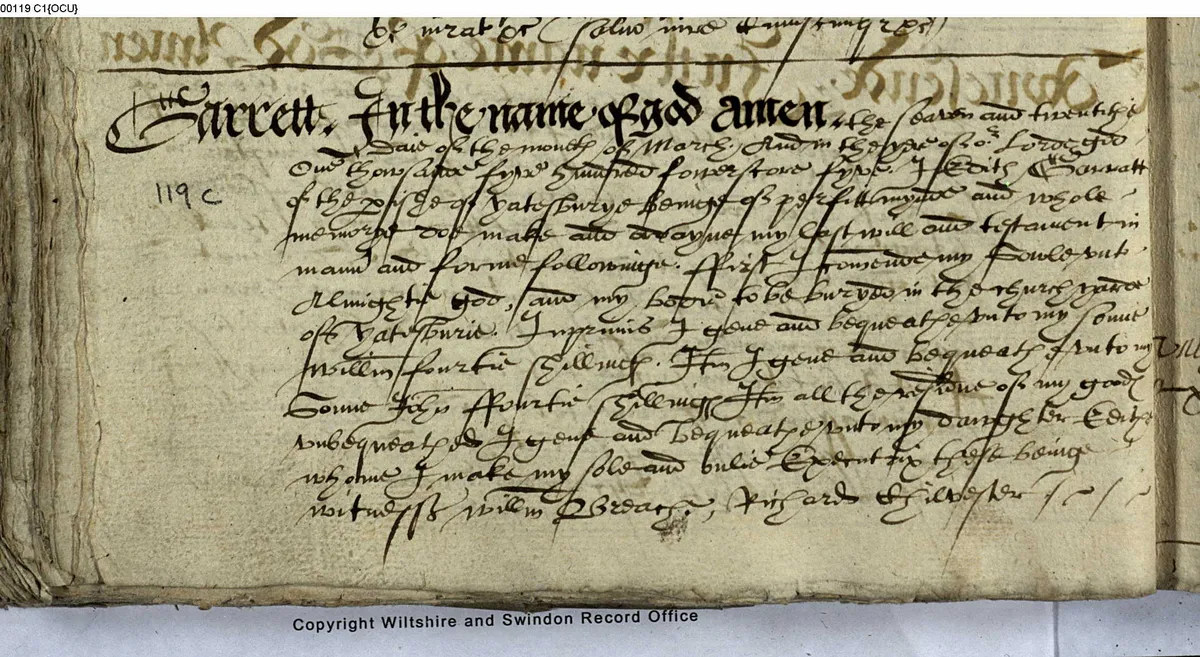

Reading a handwritten historical document, such as a Prerogative Court of Canterbury will or a baptism record, is one of the most rewarding parts of family history research, allowing us to uncover our ancestors’ lives first-hand. However, it can also be frustrating when we can’t uncover the crucial information because we can’t read old handwriting.

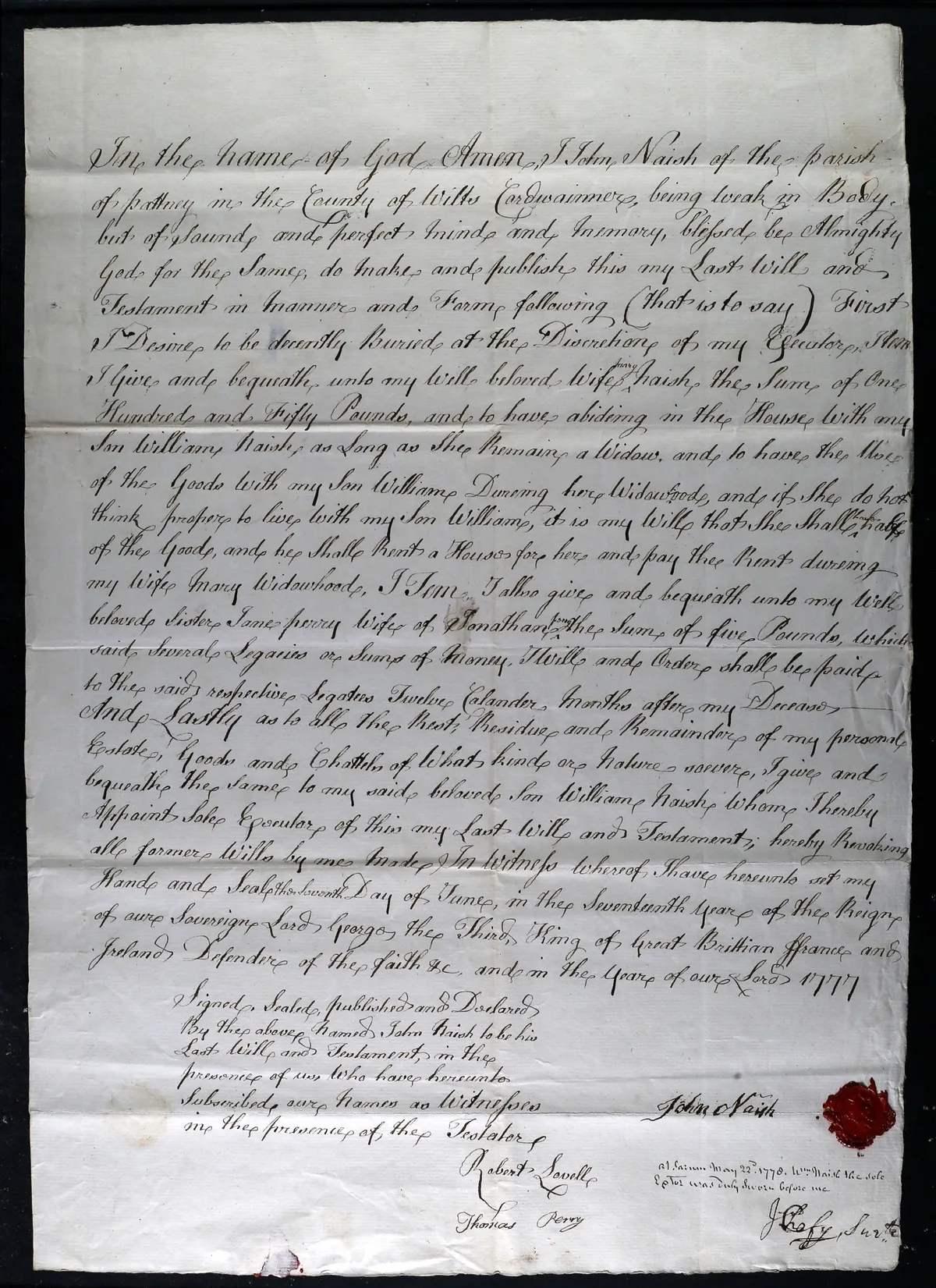

When you have a document that you wish to read, it is often helpful to make a transcription. The aim of the transcription is to make a full and accurate copy of the text. Start by reading the document as far as you can to get a sense of its meaning and to familiarise yourself with the handwriting. Next, draw up a title to describe and date the document. Number each line on the document you are transcribing and keep the same number of words per line on your transcription, retaining the original punctuation and spelling. If you are struggling to read a word, search for letters in words that you do recognise elsewhere in the document. Use these as a basis to build up your own alphabet. Also look at the context of the word for clues to its identity.

When you have a document that you wish to read, it is often helpful to make a transcription

When faced with a long document, another alternative is to quickly make an abstract. It is not always necessary to identify every word in a document, particularly if its relevance is unknown. Summarise the content by skim-reading through the document, picking out the details that have genealogical value, such as the name of the parties, the date, occupations, and place names. Draw a quick family tree to show the relationships.

How to read old handwriting: 10 top tips

- QUICK SCAN Make a quick scan of the document to get a general sense of its meaning, then number the lines you are transcribing and keep to those lines in your transcription. Also add a title that describes its content.

- BE FAITHFUL Try not to change the punctuation and spelling, although if you wish to add letters to aid comprehension, underline them so it is clear which letters appear only in the original document.

- ABBREVIATIONS If a word has been abbreviated, then put any letters you add in square brackets.

- ILLEGIBLE LETTERS If you come across illegible text, use {…} with the number of dots equalling the number of illegible characters.

- MAKE A COMPARISON If you are having difficulty making out a letter, look for an example of a similar-looking letter in another word that you do recognise elsewhere in the document.

- ADJACENCY Adjacent letters can help you to decipher a problem word.

- USE A GUIDE Consult a guide to the different letterforms associated with the hand you are reading.

- KNOW THE FORMULA Many official documents follow a specific formula, so make sure that you familiarise yourself with other examples.

- IMPROVING VISIBILITY With handwriting that is small or faint, try adjusting the contrast on your screen or increasing the magnification. It can also be helpful to print out the document and examine it under a bright light, or with the aid of a magnifying glass.

- CONSULT OTHERS If you are stuck with a word, see if someone else can help. Genealogy forums are a great place to share words that are hard to read.

How to read old handwriting: Types of handwriting

Distinct styles of writing, known as hands, flourished and were practised during different time periods. The hand that was used also depended on its purpose. Law courts and central government used Legal hand, also known as Court hand, so you will likely encounter this when viewing legal records held by The National Archives at Kew. Writing in a legible, recognisable hand that didn’t diverge much from established conventions was prized, and professional scribes known as scriveners were employed by the courts to write out or copy documents. As early as the 14th century, they formed their own livery company, the Worshipful Company of Scriveners, originally known as the Mysterie of the Writers of the Court Letter. Each law court had its own distinctive version of Legal hand, but these styles were all characterised by upright letters written closely together, and featured exaggerated ascenders and descenders.

Latin was the official language used in most documentation until 1733, after which records were written in English. The set form of these records can make reading them easier than you might expect, and they are peppered with standard phrases or words that help to identify them. For a brief period during the Commonwealth (1649–1660), such formal hands were banned – along with the use of Latin – but it wasn’t until 1731 that an Act decreed that court records should no longer be written in Legal hand. That said, Acts were still enrolled using Chancery hand – long used for official documents at Westminster – until 1836.

For a brief period during the Commonwealth (1649–1660), formal hands were banned – along with the use of Latin

In England, a style called Secretary hand was commonly used for business, personal and literary purposes from the early part of the 16th century. With increasing literacy and a growing bureaucracy, there was a need to create records using a plain style of writing. Taught using copybooks, Secretary was the hand of choice for writing provincial wills, parish registers, manorial records and private correspondence. Characterised by rounded letters with many loops and flourishes, Secretary hand was also cursive, meaning that the writer’s pen did not leave the paper. This flowing style of hand enabled documents to be written at speed.

Over time, Secretary was overtaken in popularity by Italic. This hand, which features more heavily slanted letters, was developed in Italy during the Renaissance, and became the dominant hand of the 18th century. Italic was easier to learn, simpler to read and even quicker to write than its predecessors. It also shaped other hands. As early as 1600, Secretary hand became heavily influenced by Italic script, and handwriting in general became more slanted, with increasingly pointed letters. It is therefore common to find documents written in a hybrid of the two styles. As today, Italic was often used to emphasise certain words; you may find documents written in Secretary hand but signed in Italic. In turn, Italic became influenced by Round hand, also known as Common hand, which originated in England in the 1660s. Characterised by rounded letters with looped ascenders and descenders, by the mid-18th century Common hand was growing in popularity and, over time, evolved to become closer in appearance to the common handwriting we recognise today.

How to read old handwriting: Spelling difficulties

Spelling is another troublesome area, particularly in documents written prior to the 18th century, before spelling was standardised with the development of commercial printing and the advent of dictionaries. In earlier periods, words were often written phonetically, and you’ll find considerable variation in spelling, even within the same document. Also bear in mind local dialects when decoding unfamiliar words; if you have trouble recognising them, try saying them out loud. It is common to find words with an extra ‘e’ on the end, such as ‘ordaine’, or missing the final ‘e’ – for example, ‘mak’ instead of ‘make’. Both vowels and consonants were frequently doubled or halved, giving rise to ‘allways’ for ‘always’ or ‘goodnes’ for ‘goodness’. Letters could also be exchanged, resulting for example in ‘howse’ for ‘house’ or ‘condicion’ for ‘condition’.

Before the 16th century, the English alphabet contained only 24 letters; ‘u’ and ‘v’ were used interchangeably, and ‘i’ and ‘j’ were also regarded as the same letter (although generally the ‘j’ was used only as a consonant). Hence you may find the word ‘ever’ spelled ‘euer’, and ‘unto’ rendered as ‘vnto’. Spelling tends to be more uniform in printed documents, whereas manuscript versions display more divergence. You will also find a greater variety of spelling in provincial documents compared with those produced in towns and cities.

How to read old handwriting: Punctuation problems

Punctuation was also used more sparingly in the past, and did not follow the conventions with which we are familiar today. For example, a tick was often used instead of a comma or a full stop. Marks at the end of a line may appear to be punctuation but in fact were used simply to make the line justified – in other words, to ensure that all lines in a document are the same length – so can be disregarded. A flourish served the same purpose.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the reader today is the appearance of the letters in old documents. Characters can look very unfamiliar, especially when reading Secretary hand. A lower-case ‘c’ can look like a modern ‘r’ or even a ‘t’, and a lower-case ‘r’ can look like a ‘w’. Watch out for letters with long or sloping descenders and ascenders, which can cause confusion; the position of the cross on a ‘t’ often varies, too. The appearance of letters can also vary according to their position: an ‘e’ at the end of a word can look very different from one at the beginning of the word or in the middle.

Another letter that can cause confusion is ‘s’, for which different long-form and short-form versions were used; the long ‘s’ can be mistaken for an ‘f’. A single long ‘s’ was typically used at the beginning of a word, or in one that would otherwise contain a double ‘s’ in the middle. The short-form version would typically be used at the end of a word, even if it ended with a double ‘s’. Minims such as the letters ‘n’, ‘m’ ‘u’ and ‘i’, formed by the single downstroke of the pen, are another tease because they can be hard to distinguish if the joins are not clear.

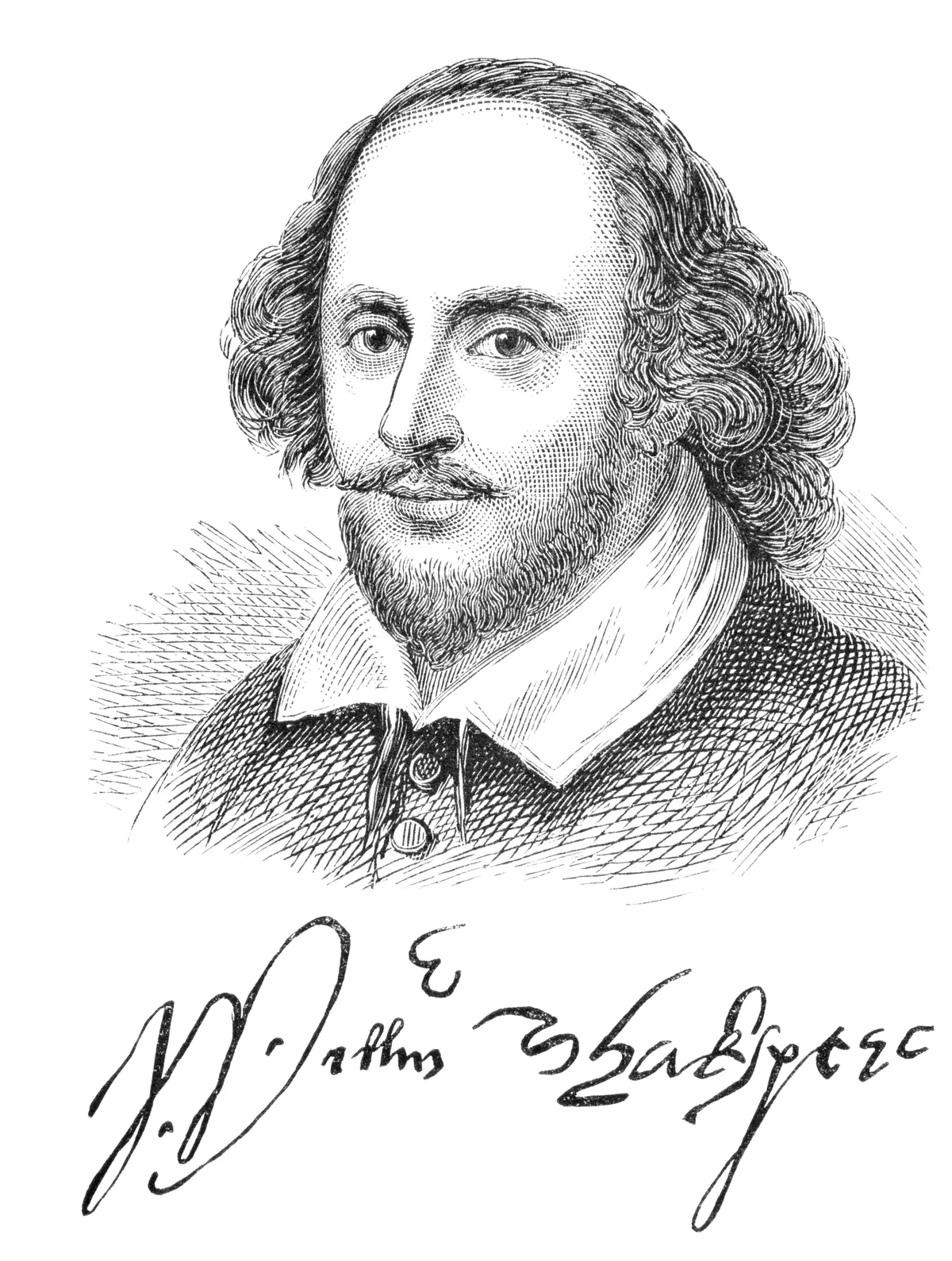

In general, the names of both people and places can be the most difficult to decipher, because of the lack of context and the creativity in spelling. Indeed, even that most literate of men, William Shakespeare, signed his name variously William Shaksper, Wm Shakspe, William Shakspere, Willm Shakspere, William Shakspeare and even Willm Shakp.

English names were also often Latinised – for example, Johannes for John. The Greek letter Chi, which looks like a capital ‘X’, was used as a symbol for Christ (hence Xmas). This means that the name Christopher may be recorded as Xopher. Names might also be abbreviated, so you might see Chas: for Charles, Jno: for John and Ed: for Edward.

Capital letters were frequently written in a variety of decorative styles and, because they appear more rarely, it is not always possible to find other examples in a document for comparison purposes. Capitals were used randomly, too, not just at the beginning of sentences. Note that in Secretary hand, a capital ‘F’ was written with a double ‘f’ in lower case.

Numbers may be another source of confusion. It is common to find Roman numerals (usually lower case) used as well as Arabic numbers. English money was produced in three denominations, denoted in earlier times by ‘Li’ for pounds (sometimes formalised using ‘£’), ‘s’ for shillings and ‘d’ for pence; in addition, a ‘1’ at the end of the number could be represented by a ‘j’. Hence three pounds, two shillings and seven pence could be written as iii Li, ii s. vijd.

To write more quickly and to save space on the paper, abbreviations were used liberally for words in common use and for those that were easy to understand given the context. Contractions – omitting letters from the middle of words – were common: you’ll find ‘wd’ for ‘would’, and ‘itm’ for ‘item’. The modern titles ‘Mr’ and ‘Mrs’ are survivors of historical contractions of ‘Master’ and ‘Mistress’. You may also find a suspension: an abbreviation where letters are missed off from the end of the word. One common example is ‘gentl’ for ‘gentleman’.

One clue that a word has been abbreviated is a dash or an accent, known as a tilde (~), above the missing letter(s) or at the end of the word. For example, a tilde above ‘-con’ or ‘-ton’ indicates that the ‘i’ is missing in the endings ‘-tion’ and ‘-cion’. Superscript letters may also indicate missing letters, for example ‘which’ could be written as ‘wch’ with a dot underneath.

Brevigraphs are another type of abbreviation where a symbol or stroke was used in place of letters. A brevigraph that we still use today is the ampersand ‘&’. The Anglo-Saxon thorn ‘þ’, a letter that no longer exists in the English language, is behind the very common brevigraph of ‘ye’. Over time, this letter started to resemble a ‘y’ so ‘the’ was written as ‘ye’ and ‘that’ was written as ‘yt’, although one should always record the modern-day equivalents. This is the reason why you may come across ‘Ye Olde Tavern’ or ‘Ye Olde Tea Shoppe’, names chosen for their historical resonance.

How to read old handwriting: The best websites

1. Cambridge University

The university offers free online instruction in English handwriting, 1500–1700, which includes some 30 transcription exercises, graded by level of difficulty.

2. Exeter University

View 80 digitised and fully transcribed depositions relating to 20 cases that were heard in the church courts and quarter sessions between 1556 and 1694 across the counties of Devon, Hampshire, Somerset and Wiltshire.

3. National Records of Scotland

This online tutorial based on Scottish documents includes many examples and transcriptions, plus there is a weekly poser for fun to help you to improve your palaeography skills.

4. The National Archives

The website of The National Archives at Kew has a practical online tutorial on reading old handwriting, 1500–1800. There is also a useful introduction to reading Latin in old documents with a series of lessons on different topics.

5. University of Hull

This is another useful guide, and includes exercises and tutorials to help you make progress.

6. Yale University

Kathryn James created this guide to Secretary hand in August 2020 while she was a curator at Yale University’s Beinecke Library. The guide is written as a seven-day introductory course, with two quizlets and 10 reading exercises, and covers such topics as numbers, money and abbreviations.