For centuries Britain was known for its wool, but in the mid-18th century, as raw cotton became more easily available from America, cotton spinning and weaving became established in regions where the climate was damp enough for processing it. By 1812, cotton had overtaken wool as Britain’s main export – a position it would maintain for over 100 years.

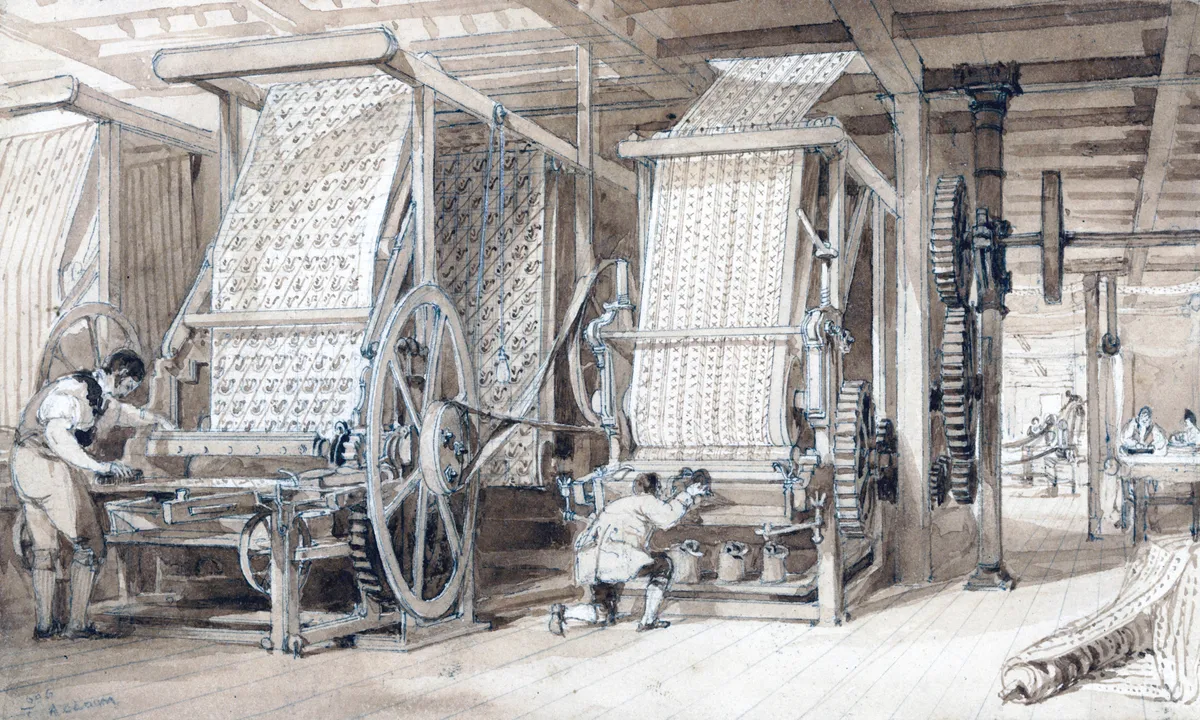

When the cotton industry began, weaving was a skilled, home-based, artisan trade. Industrialisation in Britain influenced textile production the world over. The first significant developments happened in the late 18th century. In 1733, John Kay patented his ‘Flying Shuttle’, and in about 1764 the ‘Spinning Jenny’ was invented by James Hargreaves. Around the same time, Richard Arkwright constructed a spinning machine that became known as the ‘Water Frame’. These were followed by many others and eventually every stage of cotton production was highly mechanised.

Some mills were steam-driven while others used water power. They were built near accessible sources of coal, or on fast-flowing rivers. Because of its power and climate requirements, the cotton industry was concentrated in Derbyshire (where Arkwright erected his first mill), the Clyde Valley in Scotland and Lancashire – especially around Manchester, which became known as Cottonopolis.

Although eventually mills were multi-purpose, originally the two main processes of cotton production were quite separate. Spinning mills were based in south Lancashire, while the weavers were based in the north of the county.

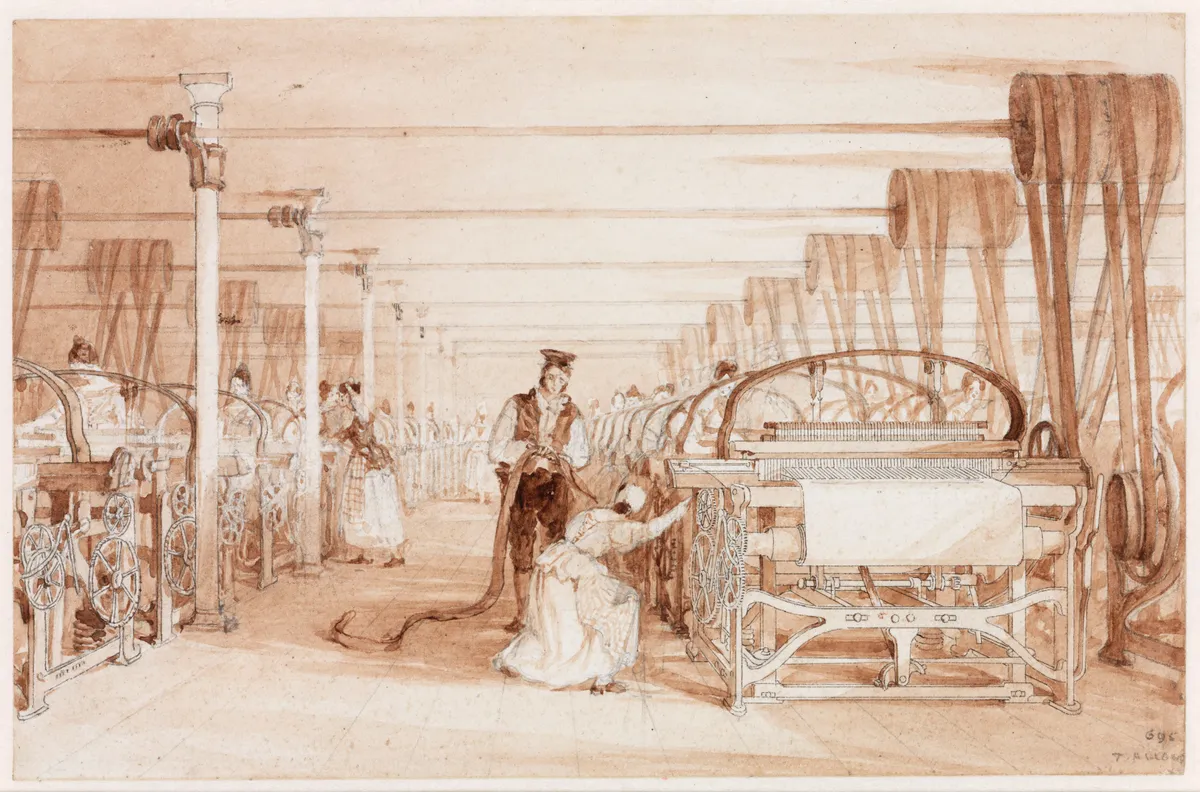

Rapid industrialisation of the mills created new jobs – not only for local men, but also for women and children. Female cotton mill workers could potentially earn the same as male, and a small number became the highest-paid women industrial workers in Victorian Britain.

Children were used for the many mundane and often dangerous jobs that required someone small and quick to work between – or even beneath – the machines while they were running. With no rules on maximum hours, children worked the same long days as adults, and many industrial accidents occurred due to fatigued children falling into or under machines.

Loud machinery in the weaving sheds often caused deafness, while respiratory or lung disorders resulted from inhaling air thick with cotton dust and fibres in the spinning mills. This would have been worse on the ground floor, where raw cotton was processed in the ‘blowing room’.

For the production of fine cottons, both the spinning mills and weaving sheds needed to be hot and humid. Sometimes steam was pumped into the room to achieve the desired atmosphere.

The daily life for cotton mill workers was harsh. Many spent a lifetime in the industry, beginning as children working half-time. On leaving school, they would become full-time, working their way through different jobs within the mill – maybe eventually going on to become an overlooker (manager).

Often whole families would be employed in different jobs within the same mill, relying not only on the father’s wage, but on the combined income of other family members. Wages were paid as piece work rather than a set amount, so the money mill employees took home was entirely dependent on the amount of cloth or yarn they produced in a day.

Cotton workers were among the first to band together into friendly societies and then unions. They used riots, strikes and petitions to campaign for better working conditions and fairer pay. The political activism of Lancashire mill workers also exerted influence in Westminster. This group was unusual in gaining a voice both within Parliament and national newspapers.

The Factory Health and Morals Act was passed in 1802, specifying that working hours for children in the mills was not to exceed 12 hours a day. This was only the first of many changes in legislation, and the workers themselves actively campaigned for improvements. Even the child workers organised themselves into committees. In 1836, the Manchester’s Factory Children Committee wrote to the House of Commons, stating: “We respect our masters, and are willing to work for our support… but we want time for more rest, a little play, and to learn to read and write. We do not think it right that we should know nothing but work and suffering, from Monday morning to Saturday night, to make others rich. Do, good gentlemen, inquire carefully into our concern.”

Although life working in the mills was hard, sociable, close-knit communities developed as most people in a town were involved in the same trade. Cotton mill workers in Lancashire enjoyed an annual holiday known as Wakes Week. The mills would shut for a week and the whole workforce would go on holiday, often to the Northern seaside towns such as Blackpool, Skegness or Morecombe.

Mills were built using new and innovative designs, specific to the different processes involved in cotton production. Spinning mills were usually built five or six storeys tall, with as many large windows as was structurally feasible, to allow in as much daylight as possible – especially on the upper floors. The raw cotton would be processed on the ground floor and would then go through various steps of processing until the yarn was finished on the top floor.

Oil used to lubricate the machines soaked into the wooden floors and this combined with the hazard of gas lighting, meant highly flammable spinning mills often accidentally burnt to the ground.

By comparison, the weaving sheds were usually single storey (the heavy looms could not be supported at higher levels), with no windows at all but with half-glazed roofs facing as close to north as possible to give a constant level of daylight without direct sun. The density of workers in weaving sheds was far higher than in the multi-storey spinning mills.

Local mill owners began to realise that their workforce would be more efficient if workers didn’t have to travel too far to work. And so they built mill cottages (and later whole streets of terraced houses) to rent out to their workers. In many census records these streets of houses are identified as belonging to the mill. For example, in the 1851 census, returns for Walsden, Lancashire, James Eastwood (who worked as a cotton engine feeder) lived in a cottage “owned by Law brothers” with his six children, four of whom also worked in the mill.

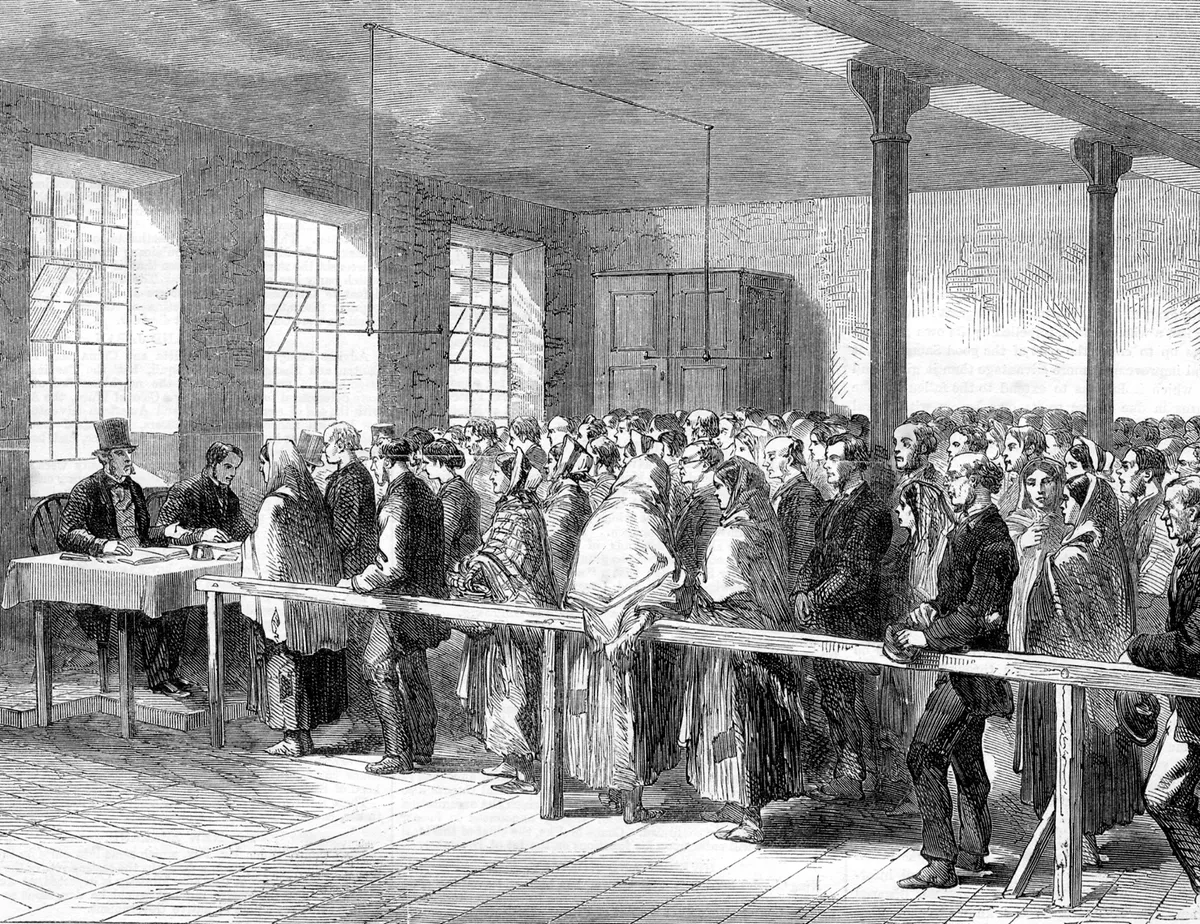

The cotton industry foundered when the American Civil War in 1861-65 disrupted the supply. This resulted in mill closures and the Cotton Famine, which caused poverty and death among mill communities.

The industry saw several such periods of boom and bust, but by the 1920s the British cotton industry was in fatal decline, largely as a result of competition from Japan. In addition Britain was losing its main foreign export customers. Having had its own cotton trade quashed in the 1700s, in the 20th century, India (until then one of the largest importers of British cotton) decided to make a political statement by boycotting all British cotton goods. By the 1970s, virtually all of the once-magnificent mills were shut.