Divorce was almost unheard of in 19th-century Britain, and highly scandalous. An Act of Parliament was required to approve each petition, and the process was costly and time-consuming. As a result, many couples who fell out of love stayed married but cohabited with new partners.

This was not always the case, however, and multiple marriages can lead to confusion for family historians. Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine reader Annabelle Long explains how she solved one such mystery with the help of a fellow family historian and a DNA test.

My Brick Wall

In 2019, I wrote to WDYTYA? Magazine about a conundrum that had fascinated me for 26 years. It centred on my great great grandfather William Chard, a labourer born in the Somerset village of Ston Easton in 1832.

I knew that William married my great great grandmother Mary Gibbons in Wells, Somerset, in 1862. Intriguingly, they married in the register office, which was an unpopular choice at the time.

William stated that he was a bachelor and Mary was a spinster. They lived in Bridgehampton, not far from Yeovilton, and had four sons including my great grandfather Henry Chard.

The conundrum arose just after I started researching my tree in the early 1990s. I was contacted by fellow researchers who were also interested in the Chards.

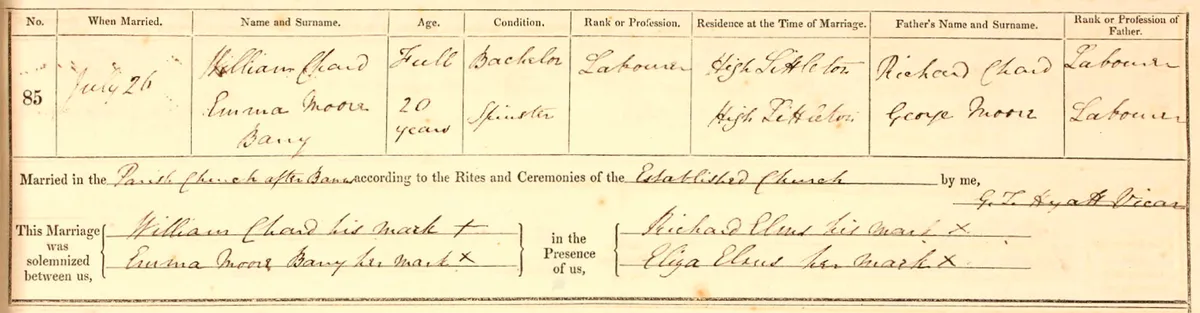

I was very perplexed to receive details of William Chard’s marriage to Emma Moore Barry in 1857. The couple got married in High Littleton, Somerset, and William gave his father’s name as Richard Chard, labourer. This matched the details on the register office certificate from William’s marriage to Mary in 1862.

I was sure William was the groom at both marriages, but I couldn’t find a death record for Emma Moore Barry until 1866. Had their marriage been annulled because William was convicted of theft in 1858 and imprisoned?

The web became even more tangled when I discovered that Emma Moore Barry had a child called William Charles Chard. He was born in July 1863, 10 months after William senior married Mary Gibbons. I couldn’t find a divorce record for William and Emma, so I decided to consult the experts at WDYTYA? Magazine, and my question was published in the August 2019 issue.

My Eureka Moment

The magazine’s contributor Nell Darby suggested that William had indeed committed bigamy, but that wasn’t the real revelation. Another reader named Judy Day contacted me via the magazine and we began corresponding. She had done extensive research into the Chard family, and could trace her husband’s tree back to Emma Moore Barry and William Chard.

In 1863, Emma was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for stealing a pan (it was her second conviction for theft) and she began her sentence in Taunton’s Wilton Gaol. Her son William Charles Chard was born while she was in prison, and his birth was registered in Taunton.

The certificate stated that the father was William Chard, but Judy and I were sceptical. Before Emma was arrested, she had been living with a man called Charles Sage. Judy and I believed that he was probably William Charles Chard’s father, even though the birth certificate said otherwise and Emma had given her son her married name.

We decided to have our DNA tested, and my 90-year-old mum Stella and Judy’s daughter Caroline also took part. Eureka! The results proved beyond all doubt that William Chard was the father of William Charles.

Judy and I were staggered by this. It meant that in 1862 William Chard, who had just been released from prison, married Mary in September and fathered a child with Emma in autumn of that year.

How could he have lived a double life, travelling 27 miles between High Littleton and West Camel when the options for transport were so limited? More astonishing details of his life were to emerge.

My Breakthrough

Old newspaper records revealed that William had a long history of theft. At various times he stole a silver watch, a waistcoat, a silk tie and headstall chains from the Bath troop of the North Somerset Yeomanry. He even stole money from his father.

However, there may have been mitigating circumstances for some of William’s behaviour. In 1878, he was admitted to the Somerset and Bath Asylum in Wells and the admission notes stated that he had kleptomania and epilepsy after being struck by lightning as a child. Such a traumatic event surely had an impact on him.

William Chard was readmitted to the asylum in 1880, and his case notes reveal that he was prone to mania and kept trying to escape. He died there aged 49 of “atrophy of the brain”.

I have sympathy for William because he had a sad life and prison must have been awful, especially given the problems with his mental health. However, it’s good to have some closure on this episode and to have connected with Judy through the help of WDYTYA? Magazine.

Do you want to ask our panel of experts about a family history brick wall? Get in touch on wdytyaquestions@immediate.co.uk