For many of our ancestors, the workhouse – and the poor relief system of which it formed a major part – loomed large in their lives. For those in need, it was the welfare system of its day, providing help for the homeless, the unemployed, the sick, the physically and mentally incapacitated, parentless children and single mothers.

Originally based around individual parishes, an overhaul of poor relief in 1834 created new administrative areas – groupings of parishes known as Poor Law Unions – each with its own workhouse and run by a locally elected Board of Guardians. A central body, the Poor Law Commissioners (PLC), oversaw the operation of the new system.

Keeping costs down was a constant concern for the administrators of the relief system and for the local ratepayers who funded it. That meant minimising expenditure and keeping a tight rein on those to whom assistance was granted, especially by a clamp-down on providing out-relief – handouts in the form of cash or kind, such as bread. From 1834, it was intended that able-bodied men and their families were to be deterred from seeking help by making the workhouse the only form of relief on offer.

The PLC introduced an extraordinary level of bureaucracy, with a vast array of record books and forms that unions would require in order to carry out their responsibilities. Fortunately for family historians, those that survive can provide a wealth of information and it definitely pays to explore beyond the most obvious records such as admission and discharge registers.

For someone unable to put food on the table, or to pay their rent, seeking help from the union might be their only practical option. The usual first point of contact with the relief system was not to knock on the door of a workhouse, but to contact one of the union’s front-line officials, the Relieving Officers, who regularly visited each parish in the union and assessed each applicant’s individual situation.

A claimant might well be hoping for out-relief which, despite the PLC’s aims, continued to be the overall most frequent form of assistance. Those receiving and accepting the offer of the workhouse were given an admission ticket and made their own way there, potentially a walk of up to ten miles, accompanied by their family, if any.

In some cases, there might be doubt over an applicant’s eligibility for relief. This was particularly the case in urban unions, where claimants were more likely to be unknown to a Relieving Officer. The law of settlement still applied after 1834, meaning a union was only obliged to assist those who had legal residence status in one of its member parishes. Alternatively, a claimant might have relatives who, as the law required, should be supporting them. In such cases, an investigation could be undertaken to gather the relevant details.

Note that the workhouse system was in place in England and Wales - Scotland had a separate Poor Law system.

Where can I find workhouse records?

Few workhouse records are online, so the best place to start is often the County Record Office local to the institution. You will need to know roughly when your ancestor was in the workhouse and, if it was after 1834, which Poor Law Union their parish belonged to. Local record offices can be found on The National Archives' Discovery database.

The Workhouse website is the best place to go online to find out about the history of a particular workhouse or Poor Law Union, with plenty of pictures and old maps. It also has some information about the workhouse record holdings for particular institutions.

Those workhouse records that have been digitised will mostly be found amongst large regional collections on family history websites. For example, Ancestry has online collections from the London Metropolitan Archives, including London workhouse records. It also has collections for places including Warwickshire, Norfolk, Bedfordshire and Cardiff.

Findmypast has also put workhouse records online for Kent, Cheshire, Surrey, Monmouthshire, the Manchester area, and also some in Ireland.

Remember, a death certificate revealing that an ancestor died in a workhouse from the late 19th century might not mean they were in dire poverty, as by then workhouse infirmaries offered the best form of free medical care. Infirmary registers are usually kept separately to workhouse admission registers. Use the Hospital Records Database to find workhouse infirmary records.

Types of workhouse record

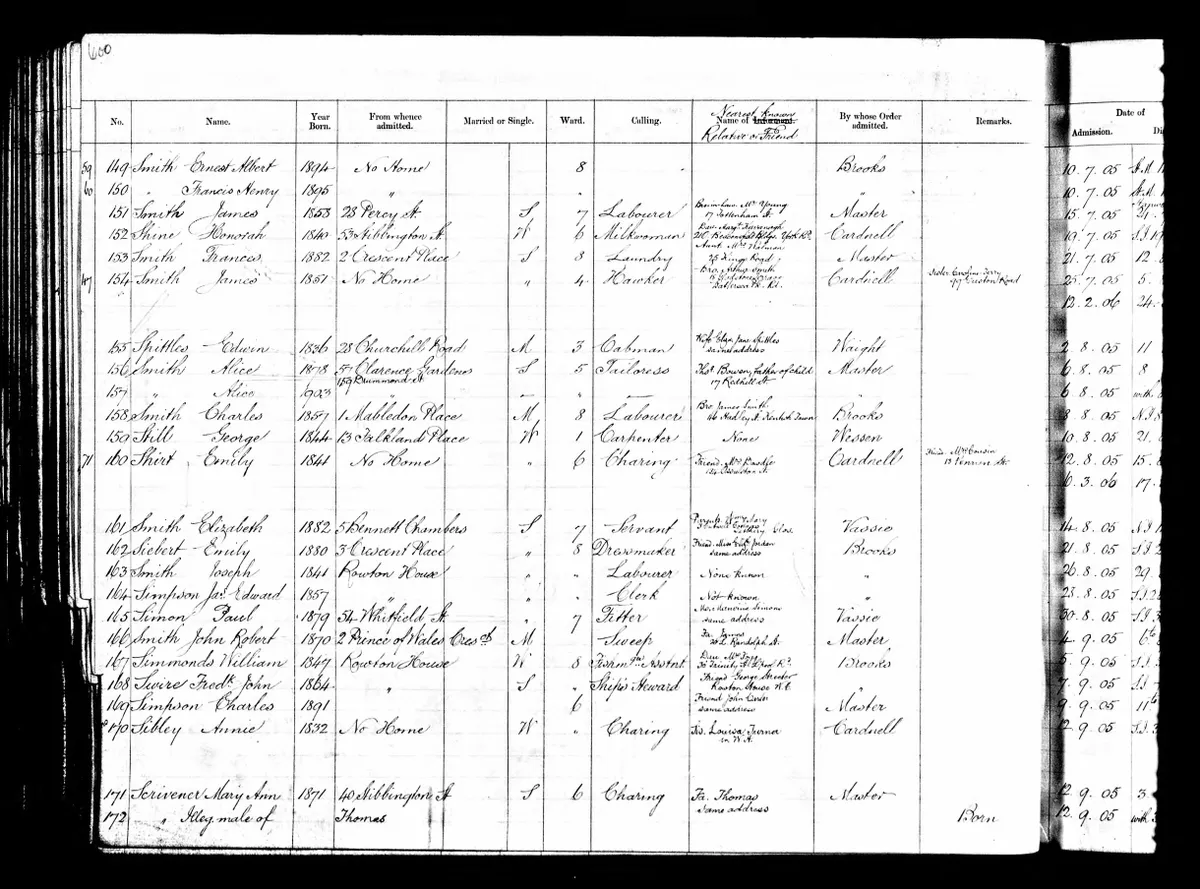

Workhouses maintained various sets of registers to keep track of inmates. Admission and discharge registers and ‘day books’ are among the most common workhouse records. They're usually arranged chronologically, listing the names and biographical details about people arriving and leaving the workhouse.

Many paupers ended their days inside, so deaths are commonly noted in these workhouse records. Creed registers recorded an inmate’s religion, but can often provide just as much information as an admission register.

The Poor Law authorities had the right to refuse relief to people who could not prove that the parish or Union was their legal place of settlement, and could pay to transport the pauper and their family to wherever they were legally deemed to belong. The criteria for legal settlement changed with various amendments to the Acts, but often paupers were removed to the parish where they or their parents were born or formerly lived. You will sometimes see Settlement Certificates, Examinations and Removal Orders among workhouse records.

Children born out of wedlock were a particular drain on parish resources, since any child born in the parish might legally be entitled to settlement there. As a consequence, it was not unheard of for officials to forcibly move heavily pregnant women on with a Removal Order.

From the 16th century, parish officials could hold Bastardy Examinations, interviewing the mother of an illegitimate baby to ascertain the identity of the father.

Men were obliged to sign a Bastardy Bond agreeing to pay the parish for the child’s maintenance, and court records may be found amongst Quarter Sessions and Petty Sessions, particularly when fathers attempted to evade the authorities.

If your ancestor was born or died in the workhouse then their name may have been entered in the institution’s baptism or burial register. TheGenealogist has transcripts from a selection of parishes, including entries from workhouse records. Most people who died in a workhouse were buried in an unmarked ‘paupers’ grave’, so finding an exact burial plot will be difficult.

Children in the workhouse who survived the first years of infancy may have been sent out to schools run by the Poor Law Union, and apprenticeships were often arranged for teenage boys so they could learn a trade and become less of a burden to the rate payers. Some County Record Offices have catalogued apprenticeship records and Bastardy Bonds by name on Discovery.