A 15-year-old schoolboy with a precocious talent – one that might serve him well in politics – put pen to paper in 1890:

O’er miles of bleak Siberia’s plains

Where Russian exiles toil in chains

It moved with noiseless tread;

And as it slowly glided by

There followed it across the sky

The spirits of the dead.

The young Winston Churchill was reacting to the onslaught of what newspapers were calling the ‘Russian flu’, which had rolled across Britain like a storm cloud from the Central Asian provinces of the repressive Russian Empire in winter 1889.

The Russian flu was at the time the deadliest flu pandemic in Britain. It was the first to strike the country in nearly 40 years and the first truly urban outbreak, gliding from town to town by rail and passing through tightly packed terraces and soot-smeared workshops at speed.

It was also the first pandemic of the media age, and the flu’s progress across the globe was shadowed by news reports carried by telegraph to the printing presses of Europe’s capitals. By the time contagion arrived in Britain, panic was there to greet it. Dr Samuel West recorded his shock at arriving at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London one morning to find more than 1,000 hypochondriacs “clamouring for treatment”.

Cities' vulnerability

In half a century, Britain had gone from a largely rural nation to a predominantly urban one. By the 1881 census 67.8 per cent of the population of England and Wales lived in towns and cities, toiling in cramped and poorly ventilated buildings where there was no escape from the coughing and spluttering of their colleagues.

In his meticulous report to the Medical Department of the Local Government Board (published in the British Medical Journal on 8 August 1891), Dr H Franklin Parsons noted that the disease followed the steam train from London to the rail hubs in the provinces: “In the rural parts of England the market town of the district was attacked before the surrounding villages.”

The first wave, which killed an estimated 27,000 people, arrived in London in the first half of December 1889 from France, and eased off in January 1890. Although it continued to creep into the more remote parts of the country well into March, the south-east suffered the most. But the second outbreak arrived in the north, sailing into Kingston upon Hull in February 1891 and making steady progress through the agricultural hinterland of East Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire before exploding into the industrial belt of Sheffield, Leeds, Bradford and Nottingham.

From there it was carried to Birmingham, London and the rest of the country. This wave was more protracted, accounting for as many as 57,980 victims, while a third outbreak, in January and February 1892, killed 25,000. If an ancestor disappears from the records during this period, the Russian flu may be to blame. As a bleak aside, suicide in England and Wales also rose by 25 per cent between 1889 and 1892.

On 8 May 1891 the Yorkshire Evening Post reported from the heart of the second wave: “In some cases there are three, four, and five sufferers in one house. Nearly all the members of the medical profession are actively engaged day and night in visiting, consulting and dispensing, and occasionally their surgeries are besieged by persons seeking advice and waiting for medicine for patients.”

Queen Victoria's grandson Prince Albert Victor died of the Russian flu (Credit: Getty Images)

Symptoms of infection

Those afflicted endured fever, cough, sore throat, aching muscles, and swollen eyes (conjunctivitis). Thanks to a ruined immune system, patients were vulnerable to pneumonia, which caused chills, chest pain, shortness of breath, vomiting and the risk of death as their infected lungs filled with fluid. Further deaths were attributed to bronchitis and other respiratory infections, which at the time masked the full impact of the virus and gave The Times cause to sneer on 25 April 1890 that it “produced an effect on the imagination altogether disproportionate to its actual destructiveness”.

Cholera was the curse of the lower orders, but the Russian flu struck all levels of society. It even sent the prime minister Lord Salisbury to his sickbed for over two weeks, and Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor, the second in line to the throne, to his grave . “In some districts the wealthier classes are said to have suffered first,” noted Parsons, “in others the labouring classes.”

In the leafy suburbs of London it was the smartly suited businessmen commuting into the City who brought the virus home with them to their families, while in the East Midlands grease-caked railwaymen from the huge London and Birmingham Railway Company works at Wolverton were principal carriers.

For all the advances in scientific understanding across the 19th century, influenza left Britain’s medical establishment powerless. Despite the work of pioneers like Joseph Lister, Louis Pasteur and Dr John Snow, the idea that a disease could be infectious or caused by microscopic bacteria (known as the germ theory or contagion theory) was widely ridiculed. The dominant theory blamed ‘miasmas’. These were noxious vapours that were thought to be released by decaying plant matter, human waste and other pollutants.

In the case of cholera, the battle against bad smells had been an accidental triumph. Attempts to combat the noxious air involved improving sanitation and sewage that did halt the spread of contaminated water, but this did little to impede the influenza virus which was being spread by the people themselves.

A reporter from the Yorkshire Evening Post canvassed a few local doctors on 22 April 1891: “Some of them think that the disease is infectious, and the manner in which it spreads once a single individual in a workshop is attacked with it seems to bear out this view. But many others incline to the opposite belief, so that whilst some of them advise the most rigorous disinfection and isolation in the cases of those who are suffering… others equally high in the profession say that these measures are not likely to have any beneficial results.”

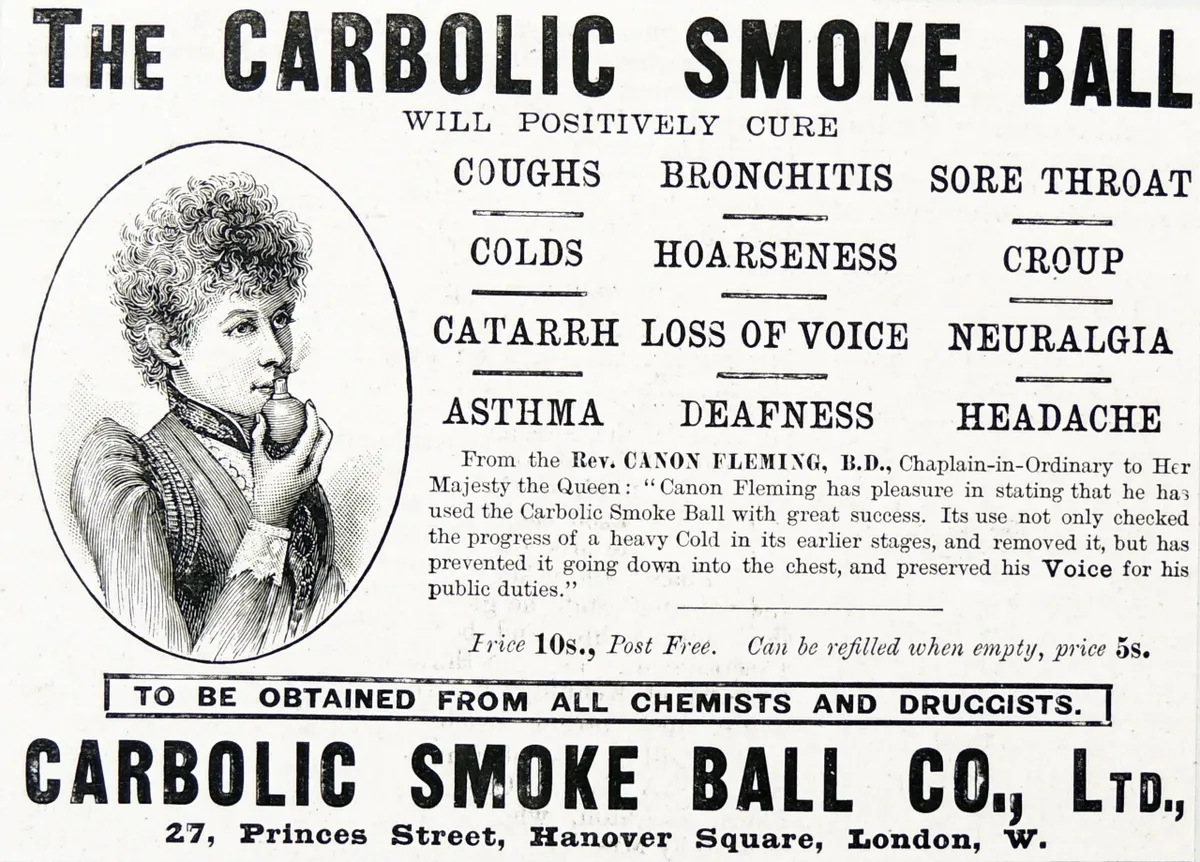

The Carbolic Smoke Ball was one of the quack cures sold (Credit: Getty Images)

Medical treatment

The best a Victorian doctor or nurse could do for their patient was give them rest, warmth, good food, clean water and fresh linen, and to isolate them as much as possible from the threat of secondary infections or from the unspoilt immune systems of their friends and family. But it was rare that patients received help that early. In the industrial sprawls of Britain – filled with factories, mills, collieries, foundries and workshops – respiratory conditions were facts of life, so coughs caused little alarm in the sufferers and few working poor could afford to miss a shift over it.

Once the flu had its grip on the patient, doctors generally treated the symptoms rather than the disease. Bitter-tasting quinine was administered for fever because it had been successful in combating malaria, but did nothing for the flu other than expose patients to the risk of side effects like stomach cramps. The anti-inflammatory antipyrine was injected to ease headaches and reduce the effects of fever with more success. A solution of sodium salicylate, a powdered antibacterial and anti-inflammatory, was injected only in the case of life-threatening fevers because of its high toxicity. This added to the death toll: the symptoms of salicylate poisoning were indistinguishable from those of pneumonia.

The failure of conventional medicine spurred on unscrupulous chemists to sell unproven pills or potions. The most infamous quack cure of the pandemic was the Carbolic Smoke Ball. A rubber ball was filled with carbolic acid, or phenol, and connected by a rubber tube to the nostrils. The ball was squeezed to release a puff of corrosive fumes which would cause the nose to run and supposedly flush away the infection. The manufacturer pledged £100 if it failed to work. One woman bought a Carbolic Smoke Ball, subsequently caught influenza and took the company to court in a landmark dispute.

Many of these remedies, from the useless to the poisonous, remained in use when the Spanish flu arrived in 1918. Although the official advice moved firmly in favour of bed rest and isolation, no thought was given to the mandatory reporting of cases or the coordination of response on a national level.

Advocates of the miasma theory persisted until the first decades of the 20th century, although the clearly infectious nature of the Russian flu had won the vast majority round to germ theory. But without steps taken to combat it or understand how it spread, this wasn’t enough.

The pandemic of 1918–1920 is often remembered as a grim postscript to the First World War, but the Spanish flu is the consequence of lessons that went unlearned by doctors combating the Russian flu three decades earlier. The estimated 228,000 who perished in Britain were the legacy of a society that ignored the warnings.